What Is My Book: Pure Story, Discursive Narrative, or a Discourse with Narrative?

Fabric, once woven, seems seamless, yet the making of it requires an intricate selection and pattern of threads to achieve the desired texture and design. A well-crafted nonfiction book also appears seamless, yet within its pages are hundreds of meticulously selected threads and a weaving of structural warp with interlocking, illustrative weft.

How does a writer go about knowing which threads to attach to the loom and which threads to weave through them? How should authors approach the task of weaving illustrations and anecdotes with straight discourse?

In the workshop of nonfiction, many overlapping and confusing terms lay scattered about, tripping up unsuspecting writers: personal essay, memoir, narrative nonfiction, illustrations, and storytelling. I see writers having a hard time not only deciding what kind of book to write but also knowing what kind of book they are writing.

The foundational layer for this dilemma—undergarments that hide from view—is a spectrum for how an author conveys a message. When you identify this foundational layer for your book, you will have a template for the structural threads (the warp) and you will know how densely to pack the weft (the interlocking complement that pulls the ideas of your manuscript into a seamless fabric).

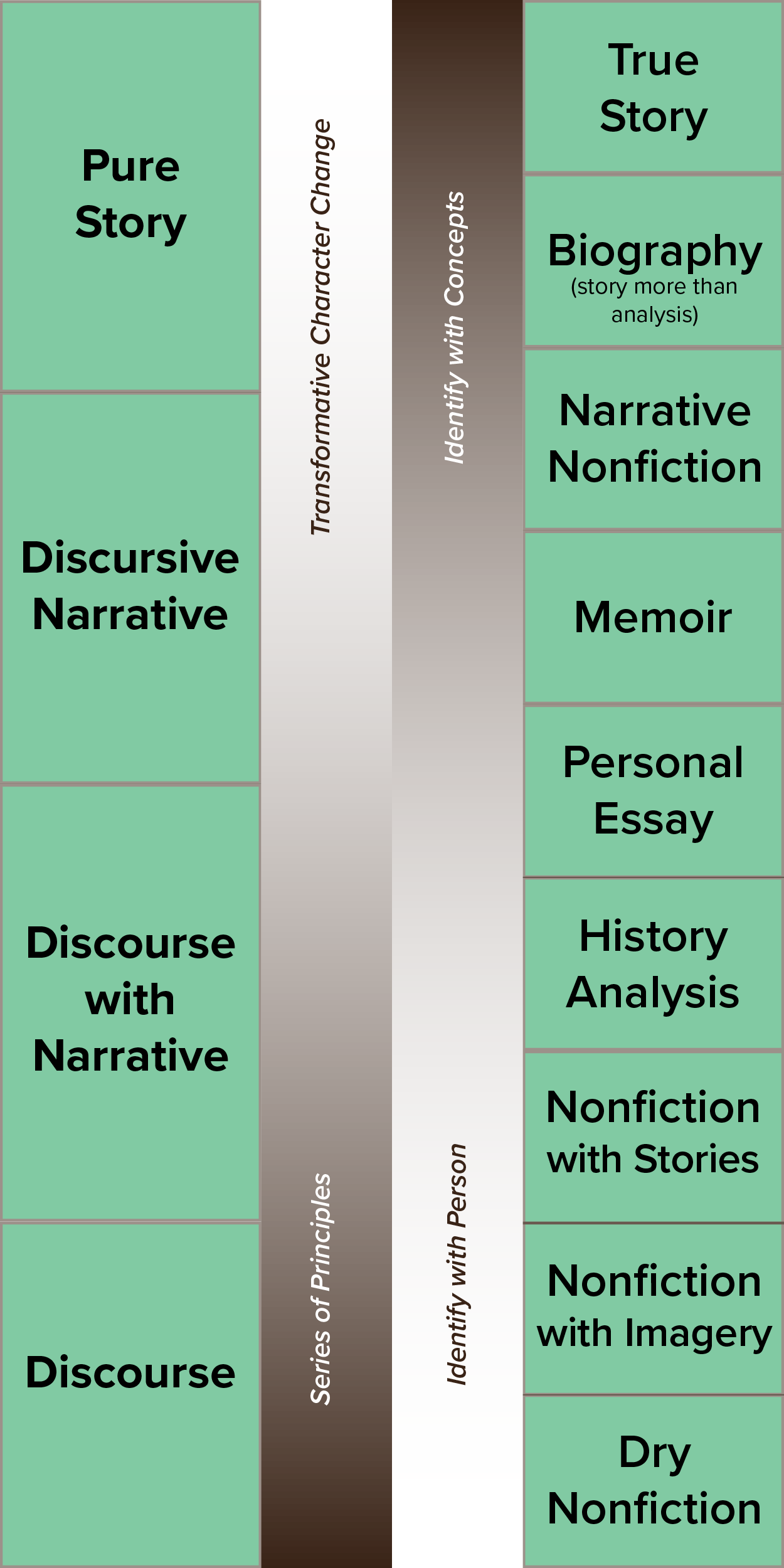

The Spectrum

The three stopping points on the spectrum (at least the three we’re going to talk about) are pure story, discursive narrative, and discourse with narrative.

Pure Story

In pure storytelling, the author creates scene after scene with little explanatory discourse in between. The Gospels fit in this category. The Gospel writers may begin or end their literary works with explicit explanations of purpose:

It seemed good to me . . . to write an orderly account for you . . . that you may have certainty concerning the things you have been taught. (Luke 1:3–4)

But these are written so that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that by believing you may have life in his name. (John 20:31)

But almost entirely, the Gospels consist of scenes and exposition of characters, setting, and plot. Readers take all the small details of character, dialogue, setting, action, and subtext to infer the meaning of the text. The narrative threads are the structural threads (warp) as well as the interweaving ones (weft).

Discourse with Narrative

On the other end of the spectrum, discourse with narrative, the author sets out to explain concepts and principles through logic and rhetoric. Personal essays usually fit here as do most general nonfiction books. For these books, the author uses illustrations or anecdotes to give concrete connections to abstract ideas or to give a real-life example of a principle. The author may use a lot of deductive reasoning or a blend of inductive and deductive to help lead readers to realize the author’s conclusion on their own.

Within the illustrations, the author must employ the skilled subtext of story, and through word choice and imagery, the author can add layers of meaning to the text, but for the most part the prose is straightforward.

Whether the stories are told in first person or third person, the author-narrator maintains a chronological distance from past events, narrating them with hindsight and at least some omniscience. The structural threads are the principles as explained by discourse, and the narrative threads, the weft, weave in and out, pulling the principles together.

Discursive Narrative

Somewhere in the middle we find discursive narrative, often in the form we call memoir, often narrative nonfiction. Discursive narrative vacillates between explicit and implicit expression. The author relies on the reader to infer meaning through the subtext of the narrative while also building a claim through inductive reasoning and occasional deductive explanation. The discourse (weft), interlacing the threads of the structural narrative (warp), takes on the color and patterns of the narrative voice to reveal a tapestry as the whole book is woven.

A distinctive element for discursive narrative, this weaving of a tapestry from the threads of lived events, is the first-person point of view. The author employs a layering of narrative distance to lead readers through the story, creating tension yet also bringing about resolution and persuading the reader to internalize the main character’s epiphany. The main character in first person, is, of course, the narrator. And this narrator exists as at least two people: the author (or persona) as he or she was at the time of the events and the author (persona) as he or she is at the time of narrating.

The discursive threading will come from the “now persona” commenting omnisciently on the “then persona’s” thoughts and choices. The now persona narrating with hindsight can build tension through foreshadowing. Yet readers also need to identify with the earlier persona to engage with the story and for tension to build; they need to wonder what causes the transformative change between the character at the start of the story and narrator’s perspective at the end. The skilled author will pay attention to which persona’s thoughts and understanding need to carry each scene, and will reveal the earlier persona through dialogue and action, as needed.

Planning the Texture of Your Book

Take a look at your content. What do you want to communicate most: the transformative change of a character (or the people around that person) or a series of principles explained by real-life events? What response do you want most in your reader: identification with a person or identification with a defining concept? How you answer those questions will help you plan the texture of your book and weave its pages together.

Kelli Sallman is a freelance editor, writer, and writing coach, specializing in fiction and narrative nonfiction, as well as inspirational and religious nonfiction. Kelli enjoys the process of helping other writers find their unique voice and story. She uses her teaching and editing skills to coach writers to improve their craft and bring their stories to fruition, and her knowledge of the traditional and self-publishing industries to help authors create platforms, get published, and get heard.

© 2018-2019 Kelli Sallman Writing & Editing

Unless otherwise noted, all Scripture taken from THE HOLY BIBLE, ENGLISH STANDARD VERSION ® Copyright© 2001 by Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission.