How to shape a riveting story from the details of your life

One afternoon several years ago, my middle child came running up the basement stairs to show me his new Lego sculpture. In the instant I turned toward him, I saw it: Complex. Artful. In that same instant, I bumped it accidentally with my elbow. The sculpture dropped and shattered into its many pieces. My eyes grew large. I looked at my son and said, “Oh, Ben! I’m so sorry!”

“That’s okay, Mom,” he said, shrugging. “It’s all in my mind. I can put it back together again.”

Here’s the difference between me and my son when it comes to Legos: He has 3-D genius and can sculpt whatever he wants out of a table piled with the tiny building blocks. I’m willing to put in the hard work, but I need directions.

I suspect that a lot of would-be memoir writers are like me and Legos—we have the building blocks and the desire, but we need directions. Good news! I know where to get those.

Memoir is a popular subset of the narrative nonfiction genre, and it seems everyone wants to try their hand at it these days. But writing good memoir brings two challenges: (1) it depends on excellent storytelling technique, and (2) it must remain true to life. In other words, unlike with a novel where the author can change facts, characters, and plot points to fit the needs of the story or add more pizzazz, in memoir, authors have to work with the bricks they have. A green, eight-prong Lego will never be a white, four-prong brick. It is what it is. Memoir authors must hone their authorial eyes to see the story that’s already there and tell it for all it’s worth.

The rest of this article is a template for how to discover the building blocks of any memoir and shape a riveting story from the details of your experience. I recommend reading through the entire process before sitting down with your notebook and working your way through the steps.

Sort Your Legos

Where should you start? Plenty of writers dive into the mess of Legos in the center of the table and start building (and writing) while in discovery mode. But unless you have memorized the inventory of bricks, you may not realize a pivotal piece sits waiting for you at the bottom of the pile. And without knowing that possibility exists, you may never dream of the shape your memoir wants to become. So let’s start by sorting our Legos.

Step 1. Assess events and conversations and memories for meaning. What did you learn? What changed your perspective? What threatened to undo your understanding of the world, your understanding of self, or your expectations of your circumstances? Where did your “aha” moment come from? Where were you when it happened? What did it feel like coursing through your mind and body? Write all these events and thoughts down. Use shorthand and notes rather than writing out scenes.

Step 2. Look for commonalities. Longer narratives need subplots and subthemes to develop the story, characters, and literary argument, and to maintain the dramatic tension. Ask the events, conversations, and memories you assessed in step 1, “How do you fit together?” Shoot up to a heavenly perspective: With hindsight, how do you now see that God was moving behind the scenes during your lowest moment, your highest moment, your greatest conflicts, and your encounters with wise counselors? Shrink down to microscope level: Which events or conversations over a span of time caused similar internal responses, whether or not you understood why? What behaviors or emotions or habits recurred throughout this time period, or over your lifetime? Do you see any of those same behaviors/emotions/habits in close family members or other influential sources? What about commonalities between your responses to your microcosms that reflect or push back on social change and cultural norms in the macrocosm?

What do I mean by that last question above? If you’ve read Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, then you’ve seen her excellent use of the literary foil technique. Scout’s main-character, first-person narration explores the macrocosm tension of racial prejudice in her culture while remaining “blind” to her own microcosm prejudice against her mentally impaired neighbor, Boo Radley. Flashing back or sub-plotting a literary foil against what’s happening at the core of your memoir can add to your literary argument, the understanding you want your reader to arrive at by the end of the story, without you having to articulate every point in so many words.

Step 3. Name the goals and obstacles. Obstacles exist both internally and externally. For instance, young Louis Zamperini, subject of Laura Hillenbrand’s Unbroken, wants adventure, respect, and glory. Externally he faces obstacles of prejudice against his Italian heritage that interrupt his search for respect, and his military service and POW internment confound his external goal of an Olympic running career, his path to glory. Internally, his own penchant for troublemaking threatens to derail his desire for respect and a successful running career.

What external goals did you have in the period your memoir covers? A career? A relationship? An invention? An accomplishment? Did those goals change over time? What external obstacles have caused you to change course or forced you to overcome them to achieve your goals?

What internal goals have you sought out? A sense of belonging in a family? Vindication? Glory? Peace and security? A sense of self-worth? Review your recurrent behaviors and emotions. Look again at your memories and commonalties. Name the common internal goal.

Be aware that what you think you’re striving for is often not what you’re actually striving for. Look at the pattern of what you have chosen and how you have behaved over what you think you want or believe. Perhaps you think of yourself as a justice-seeker or peacemaker, but you have a pattern of yelling at family members or pressing your point at all costs. Perhaps your core desire in these instances and with this behavior is not to make peace but to be validated as right or righteous.

Think also about the ways you tend to sabotage your success at achieving that goal—your internal obstacles. In the above example, you may decide that you want to be a peacemaker, but you sabotage those efforts by holding too tightly to your need for vindication. Alternately, perhaps you will realize that you don’t want to be the peacemaker at all. What you really want are relationships with people who value you as you are, but you sabotage those relationships by refusing to value your relationship partners as they are in return.

This meditation on self might go in many directions. Make sure you stay on track reflecting primarily on the situations and events that arose in steps 1 and 2, or go back and add to those steps if you find a new discovery here in step 3 that adds clarity to steps 1 and 2.

Take breaks as needed! This is tough internal work.

Step 4. Acknowledge your kryptonite and your Darth Vaders. Everyone has weak points, even Superman. Good character development in story always reveals the character’s fatal flaw, and this flaw may be the hardest issue for the memoir writer to address authentically. We like to believe the best about ourselves even as we suspect the worst. We shield our darkest tendencies even from ourselves, fearing the rejection that would happen “if they only knew.” We latch on to forgivable, rationalized faults while denying our true brokenness.

(Did you think the last step required you to be brutally honest with yourself? Step 4 requires even more honesty. Proceed with prayer.)

What are your temptations—not the iceberg you see up top, but the ones below the surface that will sink the ship? Some temptations are external, like kryptonite to Superman. What kind of pressure takes away all your ability to fight it? Some temptations are internal, like Darth Vader’s pull on Luke Skywalker. What desire threatens to make you toss aside everything you’ve ever believed in?

Are you completely drained yet? If not, you have more sorting to do. Dig deeper in that big pile. You’ll know you’re ready to move on when a pattern of events and meaning starts to come together in your mind, even if only as a shadow. In some small way groups of building blocks will call to you, “Pick us, pick us! We go together and mean something!”

Build Your Snowflake

When your events and memories start to coalesce into grouped meaning, and when you have better comprehension of who you were at the start of the time period you intend to cover and how you changed, then you are ready to start piecing together the structure of your memoir.

We still aren’t writing scenes at this stage, though I hope you did lots of journaling and exploring as you sorted through your thoughts above. We’re going to loosely borrow a structuring method from the Snowflake Guy, Randy Ingermanson. You can read his story-building theory that went viral several years ago here. But what you really need to know first is that memoir, like a novel, generally follows a three-act structure, and that the story is usually character driven rather than plot driven.

Three-Act Structure

Whether or not you’ve learned Freytag’s Pyramid or Aristotle’s theory of poetics, here are the main ideas:

1. Act 1 begins with an inciting incident and ends with a major “disaster” that forces the main character to fully commit to his or her story goal. An inciting incident is an occurrence that challenges a character and requires a response. This incident may cause the character’s concrete story goal to arise, such as an opportunity the character believes will allow him to achieve his ambition, or it may be an incident that threatens a simmering ambition, finally causing the character to actively seek after what she wants.

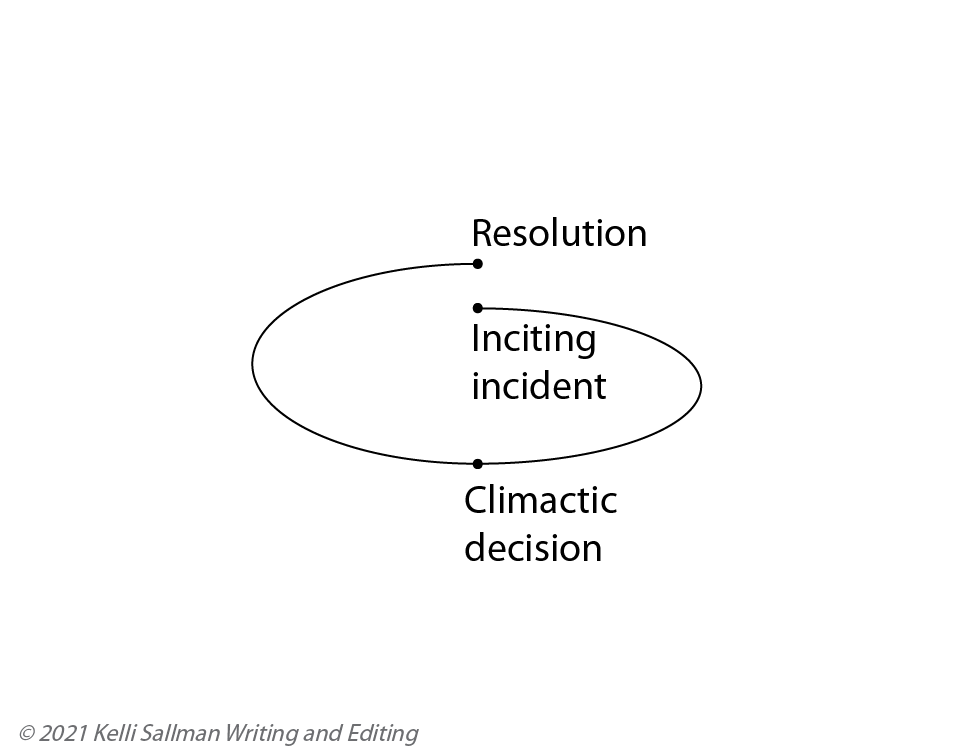

The first act presents the internal and external journey of the main character as they move into and accept the story goal, and it ends when the character fully commits to this course of action. So for instance, in Braveheart, the death of William Wallace’s father and brothers as they try to free Scotland from the tyranny of England’s King Edward sets young Wallace on his course with an ambition to free his homeland. Act 1 ends (spoiler!) when William Wallace’s new wife is killed by the king’s forces, spurring Wallace to fully commit to the rebellion. Now there’s no turning back.

2. Act 2 takes up 50 percent of the story and includes a second “disaster” near the middle that forces a big change or resolve. This big change is the climax of the story. It need not be a car chase through the streets of San Francisco or a volcano exploding. Climactic decisions are just as powerful—maybe more so—than big fights. Keep in mind this change doesn’t immediately resolve the problem, but it is the turning point that leads to resolution. A woman whose story goal is fighting a seemingly losing battle for her company’s CEO position after the board has discriminated against her finds herself facing her child’s sudden medical crisis. Overwhelmed, she considers stepping out of the CEO race. But when she pushes the hospital for a better medical solution than they prescribed, and her advocacy has a good outcome, she discovers something that leads to her climactic decision. She realizes that not only does she have the internal strength to go after the top position after all, but also that everyone is stronger when they have an advocate. She sells her car for the money to hire a lawyer to join her cause. The rest of the story will tell us whether she made a winning decision or foolishly threw away not only her job but her transportation.

On an even quieter front, perhaps the climactic decision is a parent’s realization that no matter how hard he fights for his drug-addicted, adult son, he can’t make his son do what’s best for himself. So the father changes his course, quits the battle, refuses to enable, and commits to being a safe place for his son to land when he fails.

3. Act 3 is considered the “falling” action because the outcome has already been set in motion by the main character’s choices at the climax. Now that outcome needs to play out, including one final obstacle that nearly spoils everything—but usually doesn’t.

Plot Out Your Main Story Structure

Now it’s finally time to give your snowflake—your riveting story—its scaffolding. Take a piece of paper and, in the center, draw a circle about two inches in diameter. Use this circle to plot out your story structure.

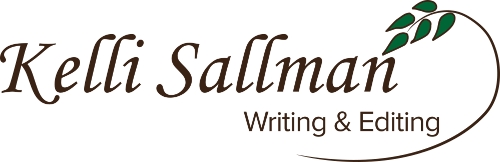

Inciting incident and climax. Look through all the events, conversations, and memories you assessed for your building blocks. Where is your inciting incident that starts the story goal? We’re going to map that on the left side of a circle, as in figure 1.

Next, find that big “aha” or decision moment, the moment when something in you changed in regard to your story goal or your inner drive. You took a stand against an injustice even though it meant permanently losing your dream job. You finally testified against your abuser. You came to realize that your past behavior abused others. You committed your life to God during a life-threatening crisis. You finally forgave your father. Put that climactic decision on the right side of the circle (see figure 1).

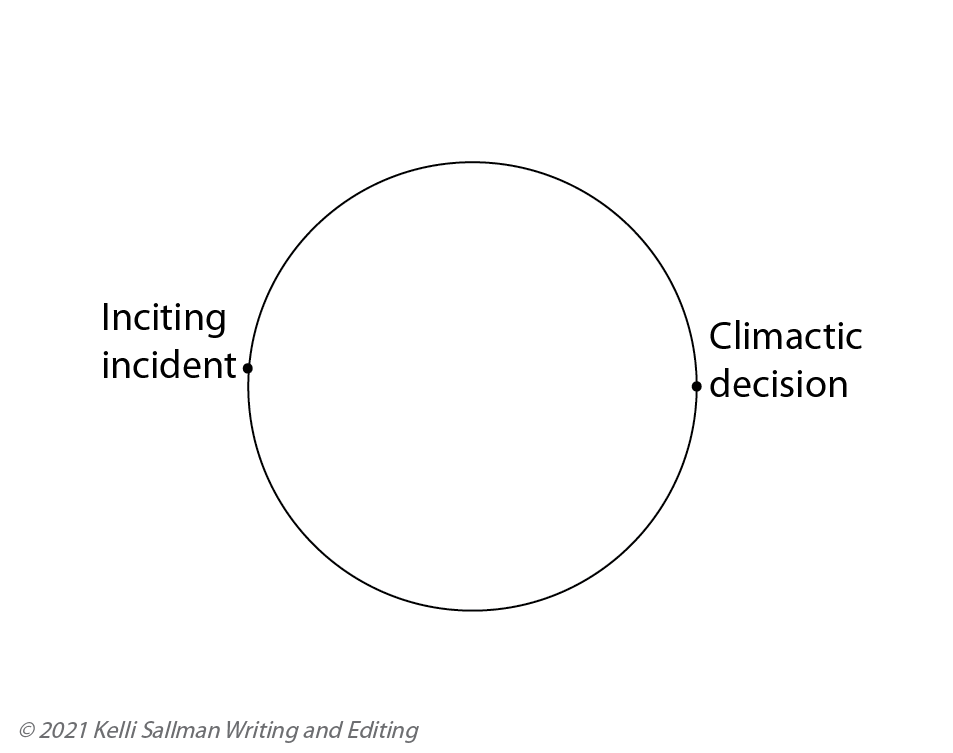

Resolution. Ingermanson begins his process with a triangle, which makes sense for how rising and falling action are generally described. But I like the circle structure because especially with memoir, the narrator’s inciting incident is usually an event that needs to be revisited. The resolution of the story usually comes full circle, not landing exactly where it started, but where it started on a higher plane. So if you look at the circle in two dimensions, we come back to the starting place, but if you look at it in three dimensions, from the side, you see the beginning of a spiral (see figure 2).

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

What building block brings your inciting incident and story goal to resolution? Your life story goes on past this point, of course, but where is the point that your core drives for this goal are satisfied, where you have either failed or succeeded and the main questions asked at the beginning have been answered? Does the main character come to faith? Does Wallace overthrow the English king or die trying? Does the wrongly jailed man finally find freedom through forgiving the brother who put him there? Map that final answer on the left, just underneath the inciting incident (figure 3).

Main character commits to story goal. Which obstacle (or character) pushes the main character to commit to the story goal? In memoir, this moment often involves some new understanding of the story problem (what the future holds) and self-awareness. Plot this block halfway between the inciting incident and the climax, at the top of the circle (figure 4).

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

Act 3 “Wrench.” What moment after the climax nearly derails the outcome of your story? Do you have a crisis of faith in your ability to achieve the story goal? Does your kryptonite or Darth Vader find your weak spot? Here’s where you need to remember that old cliché, “It’s always darkest before dawn.” In Act 3, the strongest forces come to fight the final battle. What forces are at play in your story? Spiritual? Emotional? Relational? Physical health? Financial? Self-doubt? Plot this building block at the bottom of the circle (figure 5).

Fill In the Gaps with Dramatic Tension

All that work you did sorting your Legos will come to play in this step as you add in all the blocks of character development, conflict, internal and external motivation, subplots, and so on to build out the “snowflake” fractal. On your scaffolding, you currently have a circle divided into four quarters. Your job is to look at each quarter and figure out which building block from your pile is the obstacle, speed bump, or catalyst between the starting and ending point of each quarter circle. In Braveheart, the midpoint between Wallace’s childhood determination to avenge his father and his commitment to free Scotland happens when his childhood sweetheart agrees to marry him (figure 6). (If she doesn’t marry him, her death won’t be the catalyst that forces him to commit to rebellion.)

Fig. 5

Fig. 6

What is your midpoint moment between your inciting incident and your story goal commitment? Add a point midway between these points, but outside the circle’s perimeter, and label it with this block. Keep going for each of the four quarters, finding the midpoint moments (figure 7).

Now start again at each division and find the midpoint obstacle/catalyst again between plot points (figure 8). The path from one plot point to the next should be interrupted by an obstacle, catalyst, or motivational opportunity. Figure 8 shows this second layer of obstacles (all labeled “opportunity” for ease in identification). Complex stories will have three, four, or more layers of obstacles. It’s this continual addition of layers that creates a snowflake-like fractal image for the plot structure, leading to Ingermanson’s name for his method. Keep going until you run out of blocks to fill the divisions around the circle evenly. (If you have many blocks leftover for one quarter or circle half, you may have to go back to step 1 and think through the emptier part of your story more thoroughly, or you may need to revisit the overly complex section to see if you can reduce it down to its most essential parts.)

Fig. 7

Fig. 8

Layering Your Literary Argument

Ingermanson would say that you’re ready to start writing at this point. But if you truly want a riveting story that challenges your readers to consider what they’ve read, you need to layer your literary argument over this snowflake structure before you prepare to write.

If you don’t know what a literary argument is, I’ve written about it here. In summary, each quadrant of your story structure will approach the story problem/question with a different answer/perspective/solution, directing the reader to see the insufficiency of the first three perspectives. This literary argument tracks with how your main character is changing. Perhaps the main character begins with wishful thinking, moves to cynicism, discovers faith, and finally understands true hope.[1] Perhaps the main character starts with a certain way of being—say unfiltered acceptance of her culture’s values—moves to pretending to accept them after she becomes aware of injustices, discovers a better cultural paradigm and rejects her community and their values, and then learns to merge her new values with her community by becoming a catalyst for change. Each of these moments represent a response and can be layered around the snowflake circle (figure 9).

Fig. 9

This step takes a lot of introspection, and you may not fully understand the literary argument until you begin to write out your story. That’s okay! Start with a draft idea. Consider what changes throughout the story and try to name it. The change movement will usually stay within one of these four categories: a situation (how a character’s circumstances change), an activity (how a character’s approach to doing something changes), a manner of thinking (inward process that often applies to faith and doubt; explains how characters grow in understanding/processing reality), or a state of mind (outward state that often applies to set prejudices; explains how a character’s perception of the world changes).[2] I promise you that working through this step will greatly enhance your narration and how you approach your storytelling. You may find that you need to adjust this layer as you write scenes and discover more about your story, but if you start without any argument, you will also end without one.

Review, Review, and Start Writing!

After you plot out your snowflake and literary argument, you are ready to review how the pieces fit together, make any minor adjustments that seem necessary, and pick the scenes that will make up the bulk of your narrative. Because you have done this work, now you know which scenes to include and which scenes are essential to write as full dramatic action. The reader needs to see, hear, smell, taste, and feel the obstacles and catalysts that lead to the next story point in your snowflake, and especially the four initial structural elements. Your exposition will be the connective tissue linking these scenes together.

Writing with tight prose, powerful images, and good dialogue and characterization skills will all play a role in creating a riveting story. But all the lyrical prose in the world won’t cover up poor story structure. So now you have the directions. Unfold them, sort your Legos, and start building your memoir.

Notes

[1] For my understanding on how the story problem reflects the relationship between character and plot, and how that relationship changes over the course of the story, I'm relying on Dramatica Story Theory by Chris Huntly and Melanie Anne Phillips. See Dramatica story engine software and Melanie Anne Phillips and Chris Huntley, “Dramatica Theory Book—Chapter 12: The Elements of Structure: Theme,” Storymind, accessed September 21, 2021, https://www.storymind.com/dramatica/dramatica_theory_book/chapter_12.html.

[2] These four classes of story problem come directly from Phillips and Huntley.

Resources

Randy Ingermanson, “The Snowflake Method for Designing a Novel,” Advanced Fiction Writing, accessed September 20, 2021, https://www.advancedfictionwriting.com/articles/snowflake-method/.

Melanie Anne Phillips and Chris Huntley, “Dramatica Theory Book—Chapter 12: The Elements of Structure: Theme,” Storymind, accessed September 21, 2021, https://www.storymind.com/dramatica/dramatica_theory_book/chapter_12.html.

Kelli Sallman, “How to Write a Story with a Message,” Kelli Sallman Writing & Editing, May 17, 2019, https://sallmanediting.com/resources-1/2019/5/16/how-to-write-a-story-with-a-message.

Kelli Sallman is a freelance editor, writer, and writing coach, specializing in fiction and narrative nonfiction, as well as inspirational and religious nonfiction. Kelli enjoys the process of helping other writers find their unique voice and story. She uses her teaching and editing skills to coach writers to improve their craft and bring their stories to fruition, and her knowledge of the traditional and self-publishing industries to help authors create platforms, get published, and get heard.

© 2018-2019 Kelli Sallman Writing & Editing

Unless otherwise noted, all Scripture taken from THE HOLY BIBLE, ENGLISH STANDARD VERSION ® Copyright© 2001 by Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission.